Enacting Personhood, Legitimacy, and Autonomy: What STS can Reveal about the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization Decision

Danielle Kabella, Sam Whitman, and Katie PineJuly 21, 2022 | Reflections

The recent Supreme Court decision that undermines the constitutional right to an abortion has shored up national attention. As scholars who examine reproductive health, the Dobbs v. Jackson case prompted us to reflect on the implications this has for STS. How might ethical implications of this decision extend beyond the termination of rights to a broader capacity for bodily autonomy? In what follows, we show what is at stake for people with Female Assigned Reproductive Systems (FARS) across three sites of the doctor’s office, the labor ward, and the laboratory. If the uterus is linked to policy, how we come to know it as an object of biomedical knowledge and how people enact it as a subject in embodied experiences (Mol & Law, 2004) are important for researchers in the field. Our reflection brings attention to the simultaneous dismissal of people with FARS and the establishment of fetal personhood and its reach in the pervasive network of biomedicine. We offer ways scholars can engage with already existing scholarship and activism.

As Annemarie Mol shows in The Body Multiple, the existence of objects, tools, and actors—such as disease or bodies—exists through the collection of enactments, in that doing a disease is diverse and complex. Disease is not preexisting, but constructed and reconstructed within situated social contexts as it is performed by different actors over time (Mol, 2002). In daily practice, we enact our bodies (Mol & Law, 2004). Being a person with a FARS is also fundamentally performative and multiple with its ontologies, or states of being. The following stories are drawn from fieldwork we have each conducted in the U.S. and show how reproduction is enacted across multiple sites of the biomedical system like in the laboratory in the production of knowledge of reproductive bodies and actual medical practice in a clinic.

Figure 1. U.S. Supreme Court (Source: Wikipedia. CC BY 2.0)

A young woman who had been struggling with debilitating pain during her period for most of her reproductive life had been to multiple gynecologists and other specialists for nearly 10 years. Multiple physicians dismissed her pain, telling her ‘It’s normal for women to have pain. There is nothing wrong with you.’ Eventually, she decided to try saying to her gynecologist that she was worried that she would not be able to get pregnant to see if she would be taken more seriously. To her surprise, the gynecologist began to take her symptoms seriously and ordered tests that they had been reluctant to order before. Thus, it was not until she began to frame her debilitating pain in terms of her ability to successfully conceive and carry a fetus that her pain was deemed legitimate and worthy of medical attention. The tests revealed that she had the condition endometriosis, and she finally began receiving treatment for her chronic pain after a decade of failed attempts to be taken seriously.

The contested nature of drinking even the smallest amount of alcohol during pregnancy came to the fore in the U.S. when two controversial scientific reports were issued in 2015 and 2016 from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the CDC. Both reports advised abstinence and contraception as core solutions for healthy fetal development on the basis of scientific uncertainty. This move toward total abstinence prioritizes fetal personhood over reproductive autonomy despite the science being uncertain and ultimately ties choice to morality. Every decision constituted under this moral regime is then centered around having a uterus and the potential to cause harm to a potential fetus even for those in preconception. While these recommendations open all people with FARS to state scrutiny, surveillance and prosecution of queer/trans people of color and poor white persons are especially noticeable in spaces where medical and carceral systems overlap (Paltrow, 1998; Roberts, 1997; 2022; Bridges, 2020). In the case of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, overlapping of medical and penal systems such as the labor ward and child welfare system present greater risks under Dobbs v. Jackson as reproduction increasingly becomes criminalized.

A woman is in labor; her contractions are occurring frequently since she is fully dilated. She cries in pain and asks the nurse why she is suddenly in so much pain when she has an epidural? The nurse tells her that since she is fully dilated, the epidural has been turned off so she can push, because it is ‘better for the baby.’ With each contraction, the woman writhes in pain, unprepared for the intense contractions after choosing and receiving epidural pain management for much of the labor. Seeing that the patient’s pain is uncontrolled, the nurse pages the attending anesthesiologist who ordered that the medication be turned off and requests that the patient be given more medication. She is not hopeful that her request will be fulfilled– the particular attending working that day is known for her unbending stance on medication administration during pushing. This anesthesiologist responds to the nurse’s call by coming to the patient’s room in person. The anesthesiologist takes the patient’s hand and tells her that she has to keep it together and push the baby out, then walks out of the room.

For people with FARS, the current or potential future fetus is seen as the core subject of medical care and experimentation. The cases above occur in very different corners of the biomedical system. However, power and legitimate patienthood are enacted similarly across these circumstances. In the clinic, the primary subject of medical attention is not the person seeking care from medical professionals–it is a current or future fetus that is presently or may in the future be carried by the person. The same can be said for the laboratory, where investigatory parameters center on the perception of risk at the molecular level. The material and symbolic characteristics that legitimate fetal personhood are effective in delegitimizing reproductive autonomy by narrowing choices in the scope of “risk” as matters of morality and rationality. For instance, for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, the etiology relies exclusively on alcohol because it is experimentally restricted to a narrow relationship between the birthing person and the fetus. The effects of alcohol are systematically measured from a collection of placenta biospecimens, an organ that is said to be permeable to environmental teratogens. All other environmental factors that people with FARS navigate like poverty, pollution, and racism are isolated or erased entirely. In this case, it is unclear what the teratogen is, yet the national strategy has been to focus on women’s exclusive relationship to alcohol. In some cases, even to the point of criminalization. The activist organization National Advocates for Pregnant Women (NAPW) just released a Confronting Pregnancy Criminalization guide with accurate scientific information on pregnancy and substance use. STS scholars could lend their expertise and voices to activist organizations such as NAPW.

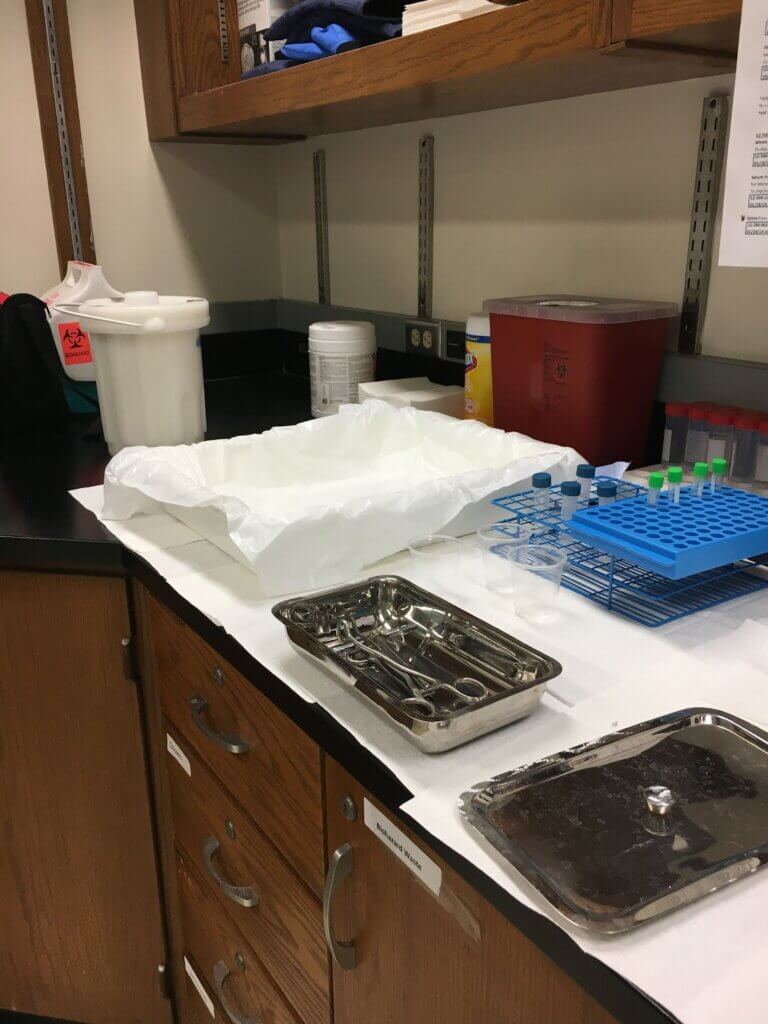

Figure 2. Placenta specimen collection table. November 13th, 2017. Photo by Danielle Kabella

STS broadly has long been concerned with the social construction of medical sciences and biomedicine (Knopes, 2019). Individuals have been found to exert agency within formal medical settings through gathering and mobilizing information about their health to establish credibility with healthcare providers, thus gaining influence over their clinicians’ diagnostic and treatment decisions (Kaziunas, et al., 2018; Seear, 2009a). STS has further shown that laypersons struggle to be seen as credible in the eyes of experts (Epstein, 1996). This line of work shows that formal organizational and institutional structures maintain the credibility of certain expert groups while not allowing other, non-expert groups (including lay persons) to achieve credibility. Importantly, our cases show the extent to which people with reproductive capacity must establish legitimacy for their reproductive medical concerns vis a vis their current or future fetuses.

A key point here is that for the medical concerns of people with FARS to be taken seriously, and for people with FARS to exert power in the biomedical system, all too often, they must establish legitimacy and credibility through their current or future fetus, not their own health, well being, quality of life, etc. Indeed, past research has found that women are treated as less credible patients when describing discomforts such as pain (Hoffmann & Tarzian, 2001; Seear, 2009b). Failure to take the knowledge and concerns of people with FARS seriously in the biomedical realm leads to systemic problems as well; these include delayed diagnosis, increased patient work, and decreased participation in work and the economy.

Figure 3. Protesters at Arizona State Capitol. June 24th, 2022.

How can we as STS scholars help to enact differently?

We argue that STS scholars have a key role to play in both researching the potential impacts of the Dobbs v. Jackson decision, and in leading to a future in which reproductive healthcare is enacted differently. STS and related scholarship extensively address reproduction, providing both empirical and theoretical tools for researching and teaching this phenomenon (see, for example, the ReproNetwork Listserv, an excellent resource for interdisciplinary scholars and activists, and the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Health Collective). As the cases above reveal, in line with past studies (e.g. Roth, 1990; Casper, 1994), locating an individual with FARS’ value in terms of reproductive capacity is not new. FARS are often rendered invisible in “technomaternal environments for fetal patients” when fetuses are constructed as entities with active agency (Casper, 1994, pg. 844). The recent supreme court decision has unveiled the politics of value of FARS’ bodies on a broad stage; something black feminists (Davis, 2019; Roberts, 2022; Bridges, 2020) have been warning us about. This is a key moment in which STS scholars and scholarship can help students across disciplines to grasp the implications of reproductive rights. STS scholarship can give students critical language around current enactments of reproductive health and how they shape science and policy.

Danielle Kabella is a Ph.D. Candidate in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at ASU. Their research interests lie at the intersections of medical anthropology and social studies of science, technology, and biomedicine.

Samantha (Sam) Whitman is a Ph.D. Student in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at ASU. Sam’s research bridges Health Services Research, STS, and Health Informatics and examines the patient work of chronic disease.

Kathleen (Katie) Pine is an Assistant Professor in the College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University whose research spans the disciplines of health informatics, Human-Computer Interaction, Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Management, and STS.

Published: 07/21/2022