STS Borderlands: Engaging science, technology, and governance from the borderlands

STS Borderlands @ ASUFebruary 21, 2022 | Projects

The STS Borderlands Collective brings together a transnational community of scholars thinking from the intersections of science and technology studies in/of the Mexican borderlands. We approach the borderlands as both a geographical space of practice and analysis and also as a generative analytical frame. We explicitly invoke the “Mexican Borderlands” to displace a focus on the meeting of the United States and Mexico and instead foreground the interconnected bordering regimes in Central and North America. As engaged STS practitioners, we highlight what activists and communities do to create just and equitable technological futures. We bring place-based critical scholarship from STS and beyond to counter bordering practices, interrogate unequal innovation, and develop a grounded, engaged borderlands STS community.

Fig. 1. Mexico-United States border in Tijuana. December 24th, 2021. Photo by Octavio Muciño

The collective was established in 2020 in the midst of the pandemic in response to our collective loss of spaces of community and collaboration. We sought to integrate our work in science and technology studies with borderlands theory, empirical research in the Mexican borderlands, and lives/learning in the borderlands. Our emergent work has focused on consolidating tools for STS pedagogy informed by the coloniality/modernity framework of Latin American studies, facilitating bilingual transnational conversations around themes of concern for the borderlands through a speaker series, and supporting ongoing research and facilitating nascent collaborations. In the next years, we plan to grow our community through a series of research conversations, an open “inverted” syllabus -an artifact that identifies academic literature produced in the Global South to shift centers the knowledge production-, and a series of workshops or working groups to support innovative approaches to writing, researching, and social action.

Mapping data, technologies, and stories

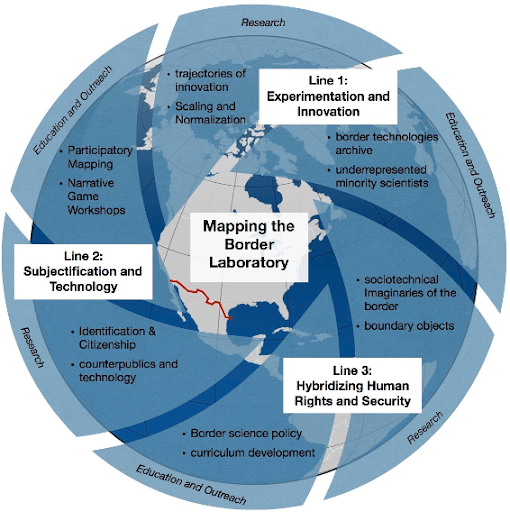

Fig 2. A schematic of our research project and the three major lines of inquiry.

Our STS borderlands research collective’s first major project has focused on the socio-technical infrastructures behind “smart” borders foregrounding the work of migrants and activists as they innovate with technology to better address their concerns, be it communication, navigation, help when in danger, family reunification, or justice. We chose to focus on four emergent border technologies: biometrics, ICT & GPS technology, forensic DNA, and isotope analysis. Although distinct in their intellectual foundations, they form socio-technical systems of border technologies at the security/safety nexus, that is they have been used by both citizen activists and state governments to address migration

Forensic DNA

In the face of the rising international outcry against the rising number of dead and disappeared migrants in the Mexican borderlands, multiple transnational and community-based regional initiatives have posited DNA as a potential solution. One prominent example, Proyecto Frontera, created in 2009, has conceived of the problem as one of coordinating multiple scientific and political regimes to allow the safe comparison of samples from victims and searching families. The US. Border Patrol also collects DNA from detained migrants and submits it to the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). In response to an emerging anti-migrant discourse focused on child trafficking, rapid test DNA technologies are increasingly used on unaccompanied minors and families crossing the border. Despite the proliferation of databases, the scale of the death and disappearance alongside the inability to share data safely and justly has raised important debates about the limit of genetic solutions.

Fig 3. DNA recollection to identify relatives of missing persons. Source: Movimiento por Nuestros Desaparecidos en México. October 20th 2016.

Forensic Isotope Analysis

Forensic Isotope Analysis (IsA) identifies the isotopic signature of elements like strontium, a mineral present in drinking water that is stored in teeth, particularly enamels. In 2008, Chelsey Juarez analyzed permanent teeth of human remains of known origins in Mexico to compare them with those of unknown origin border crossers in the US to better localize where the victim might be from. Forensic IsA for humanitarian purposes has gained advocates despite debates about its scientific validity in other contexts like immigration. Isotope analysis is built on an open science platform with researchers contributing their data to the iso-bank allowing researchers in the Global South access to data for comparison, making this technology and its governance distinct from more traditional forensic technologies.

GPS & ICT

Migrants use Global Positioning System (GPS) and Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to cross the border, navigate its harsh conditions, and share their location if they need urgent assistance. Activists offer tools (from WhatsApp groups to share risk on the way, to the collaborative offline mapping of water in the desert) to migrants so they can navigate toward rescue points or water bodies using GPS. The GPS function on phones has made them an indispensable tool for migrants. Since 2005, US homeland security has also used GPS to track migrants with pending cases using ankle monitors in the “Intensive Supervision Appearance Program.” It is estimated that BI Incorporated, the private contractor that develops these ankle monitors, has received 281.38 million US Dollars from the Department of Homeland Security so far. More recently, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is implementing an app to track detained migrants, developed by BI, using facial recognition to take pictures of the holder. This is a case where innovation in one border technology drives innovation in another border technology, like biometrics.

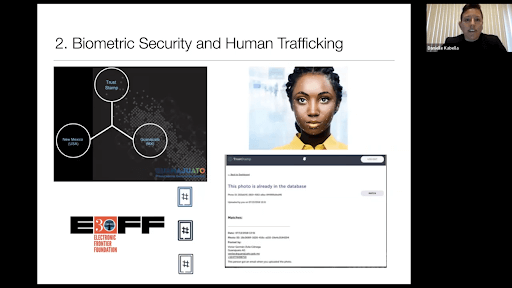

Biometrics

Detained migrants and migrants entering the US using visas must submit their biometric data to the country, and in many entry points. Since 2008, Mexico also has agreed to collect and submit biometric data of Center and South American migrants on their southern border of the Mexico-US Mérida Initiative. The US government gave Mexico 24 million dollars for equipment, including 3.5 million dollars for biometric kiosks. Activist groups in the borderlands are also using biometrics, primarily facial recognition tied to GPS technology to attempt to rescue migrants in cases of kidnapping is part of a larger trend towards the use of biometrics within humanitarian work.

Fig. 7. Screenshot from the American Association for the Advancement of Science ASU Meeting: Mapping the Border Laboratory: Knowledge, experimentation, & justice – Mexican Borderlands.

Building an STS Borderlands Community

Based on this initial research, we sought to foster dialogues about border technologies. We brought together activists, researchers, and artists living and working throughout the Mexican borderlands (Central America, Mexico, and the US) and held a bilingual Spanish/English Speaker Series in Fall 2021 focused on borderland technologies. We saw this as a first step towards envisioning and enacting pluralistic communities to understand one area of concern: security, violence, and “technologies of repair.” (Mattern 2018) As a collective, we have also identified emergent nexuses for ongoing conversations focused on environmental justice, deep time, decoloniality, and health equity. We plan to continue to hold speaker series and workshops on these themes to build conversations across and within the Mexican Borderlands. You´re welcome to join us.

You can follow our social media for future news and events:

https://twitter.com/STSBorderlands

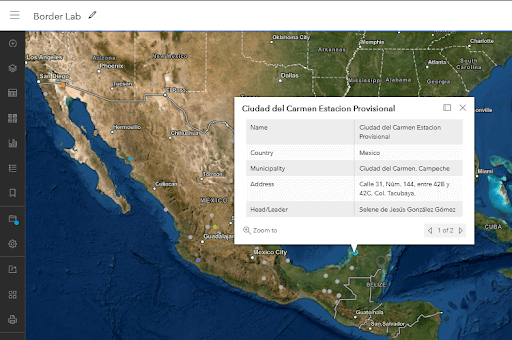

Fig. 8. ArcGIS example of our organization mapping.

_________________________________________

Octavio Muciño-Hernández is a Ph.D. student and Graduate Research Associate in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at ASU. He studies the bioethical and sociopolitical aspects of human-animal experimentation, moral imagination, selfhood, nation-states, and the liminal spaces that create such territories, like borders and their technologies.

Danielle Kabella is a Ph.D. student in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at ASU. Her research interests lie at the intersections of medical anthropology and social studies of science, technology, and biomedicine.

María Torres is a Post-doctoral fellow. She holds a Ph.D. in Philosophical and Social Studies of Science and Technology from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), focusing on genetic technologies and forensic self-organization movements in the context of forced disappearance in Mexico.

Martín Pérez Comisso is a Ph.D. student in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at ASU. His areas of expertise are socio-technical systems, engagement with Science and Technology, technological policy, and Latin American futures.

Lindsay Smith is an Assistant Professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at ASU. Her work focuses on critical forensics and human rights groups in Latin America who envision, implement and govern new technologies for justice and state accountability.

Published: 02/21/2022