“[T]he infrastructure of skirts”: Review of Kat Jungnickel’s Bikes and Bloomers

ginger coons

May 28, 2018 | Reviews

Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian Women Inventors & their Extraordinary Cycle Wear (Goldsmiths Press, 2018) by Kat Jungnickel adds to the history of women in the garment industry by focusing on female patent holders. This is a novel contribution to an existing body of literature on the practices of dressmakers, a popular topic in women’s business history. While much of the dressmaking literature focuses on the life and business of the professional dressmaker’s shop, Bikes and Bloomers addresses garments which were not necessarily made by the women who patented them. The material focus of the book is on convertible cycling garments for “lady cyclists” (lady being apposite, because class is very much at issue) in late-Victorian England. Through the stories of six women who held patents for cycling garments, Kat Jungnickel looks at Victorian women as active participants in the patenting and cycling booms at the end of the 19th century.

Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian Women Inventors & their Extraordinary Cycle Wear (Goldsmiths Press, 2018) by Kat Jungnickel adds to the history of women in the garment industry by focusing on female patent holders. This is a novel contribution to an existing body of literature on the practices of dressmakers, a popular topic in women’s business history. While much of the dressmaking literature focuses on the life and business of the professional dressmaker’s shop, Bikes and Bloomers addresses garments which were not necessarily made by the women who patented them. The material focus of the book is on convertible cycling garments for “lady cyclists” (lady being apposite, because class is very much at issue) in late-Victorian England. Through the stories of six women who held patents for cycling garments, Kat Jungnickel looks at Victorian women as active participants in the patenting and cycling booms at the end of the 19th century.

Alice Bygrave, one of the inventors profiled in this book, developed and patented a cycling skirt which was licensed to at least two different garment manufacturing firms, and appears to have enjoyed some commercial success. The story of Alice’s skirt is told through the available details of her life and context—through her childhood growing up around sewing and watchmaking; through her sister-in-law, a competitive bicycle racer. With stories like those of Alice Bygrave, the book recontextualizes invention in the 1890s as collaborative, contextualized, and incremental.

The book also attends to the doing of clothing. By interrogating patents, conducting archival research on the contexts of the women who filed those patents, and making reconstructions of the garments codified therein, Bikes and Bloomers works towards an understanding of convertible cycling skirts that genuinely considers what they did, how they did it, and who they did it for in that period.

Bikes and Bloomers empathizes with many popular STS themes, including the power of classification systems, the importance of attending to the mundane, and the insights that can be gained by questioning linear narratives of innovation and progress. It also, of course, treats the ever-popular subject of the bicycle, but with an emphasis on the evolution of garments for cycling.

The book is structured in three parts. In Part I, the author sets up the problem space, and relevant background on the development of cycling in Victorian England, Rational Dress, and the problems lady cyclists faced, including harassment and physical danger. Having presented the “dress problem” and the social milieu that gave rise to it, the author lays out a taxonomy of patent cycling garments, with the focus of the rest of the book being on the category of convertible garments. Convertibles, by incorporating mechanical elements such as straps and buttons, offered functionality both on and off the bike. The reader is told that the convertibility of these garments allowed their wearers to exercise choice about their appearance in public, gaining the benefits of a more rationally dressed cyclist while on the bike, and converting back to a familiar style of respectable womanhood while dismounted.

Part II presents five patent convertible cycling garments, the stories of their inventors, and details “interviews” of the patents, which are carried out by making and using the garments. Each of the five chapters is tied into a broader theme. So, while telling the story of Alice Bygrave’s convertible cycling skirt (chapter 6), the author also highlights the importance of collaboration to the Victorian woman inventor. With Julia Gill, a court dressmaker (chapter 7), we see an emphasis on inventiveness and engagement; Frances Henrietta Müller’s chapter (8) focuses on not only the woman herself and her better-known efforts to promote feminist causes, but on her systemic approach to change through, in this case, an entire cycling outfit; Mary and Sarah Pease (a comparatively rare team of inventing sisters) are tasked in chapter 9 with illuminating issues that accompany the visual impact of women in Victorian culture; and Mary Ward, identified on her patent as “a gentlewoman” (chapter 10), by dint of the name of her successful garment, the Hyde Park Safety Skirt, carries a narrative about fashionable cycling and the “material and discursive possibilities” of moving in public space. Part III is comprised of a brief conclusion and call to action, exhorting the reader to consider what other stories have been missed in linear and heroic narratives of technical progress.

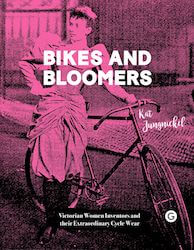

Kat Jungnickel testing the Bygrave convertible skirt. Image by K. Jungnickel.

The book is a methodologically interesting example, in that it tries to bring to life patent cycling garments from the 1890s by making them, wearing them, cycling in them, and letting others try them, too. Beyond the reconstructions of cycling clothes, stories about specific garments and their inventors (and the patents codifying them) are used to reframe innovation in the cycling industry in Victorian England. Historical patents are used and interrogated, supplemented by archival research on Alice Bygrave, Julia Gill, Frances Henrietta Müller, Mary and Sarah Pease, and Mary Ward.

Bikes and Bloomers is, in general, an entertaining and readable book. It contains novel archival research, compelling stories of women inventors, and numerous supporting images, including photos of the garments constructed over the course of the research.

Disclosure: the author of this review participated in a workshop facilitated by Kat Jungnickel and Rachel Pimm and as such, has prior knowledge of the research detailed in the book.

A researcher and designer, ginger “all-lower-case” coons studies and intervenes in the intersections of individuality, mass standards, and new production technologies.

Published: 05/28/2018